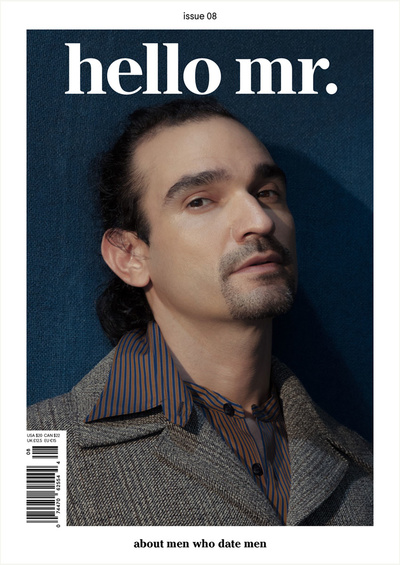

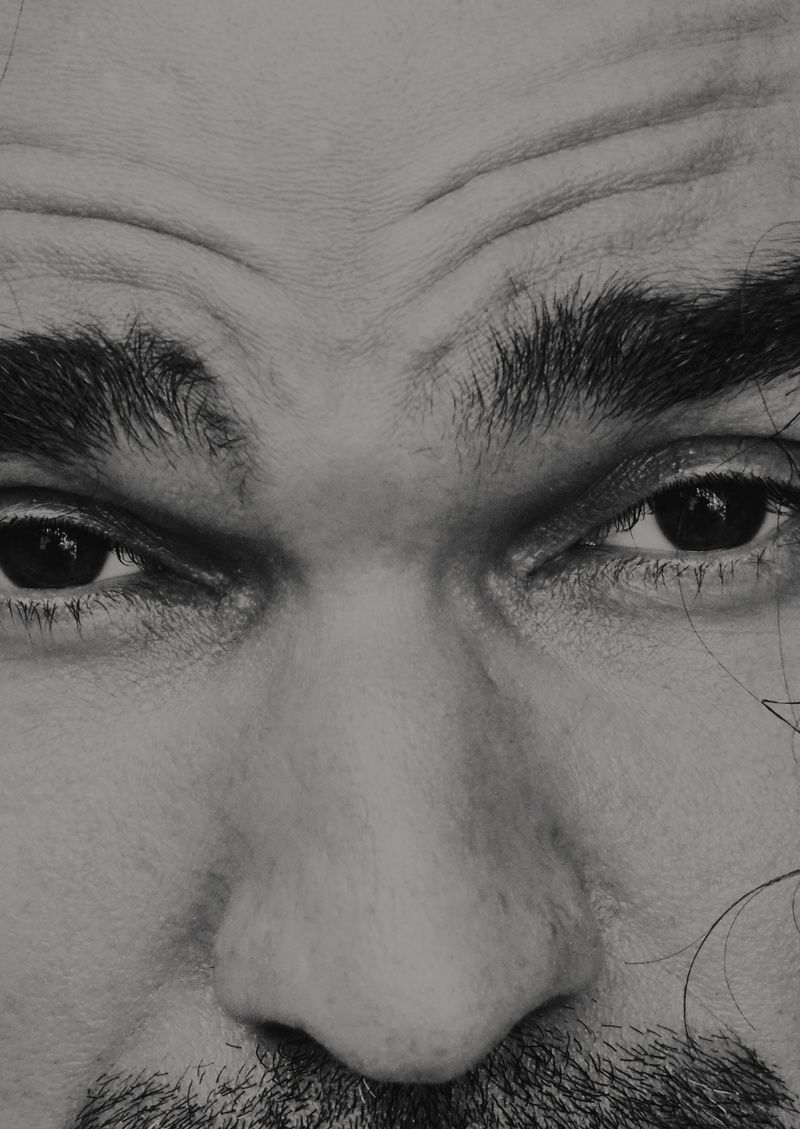

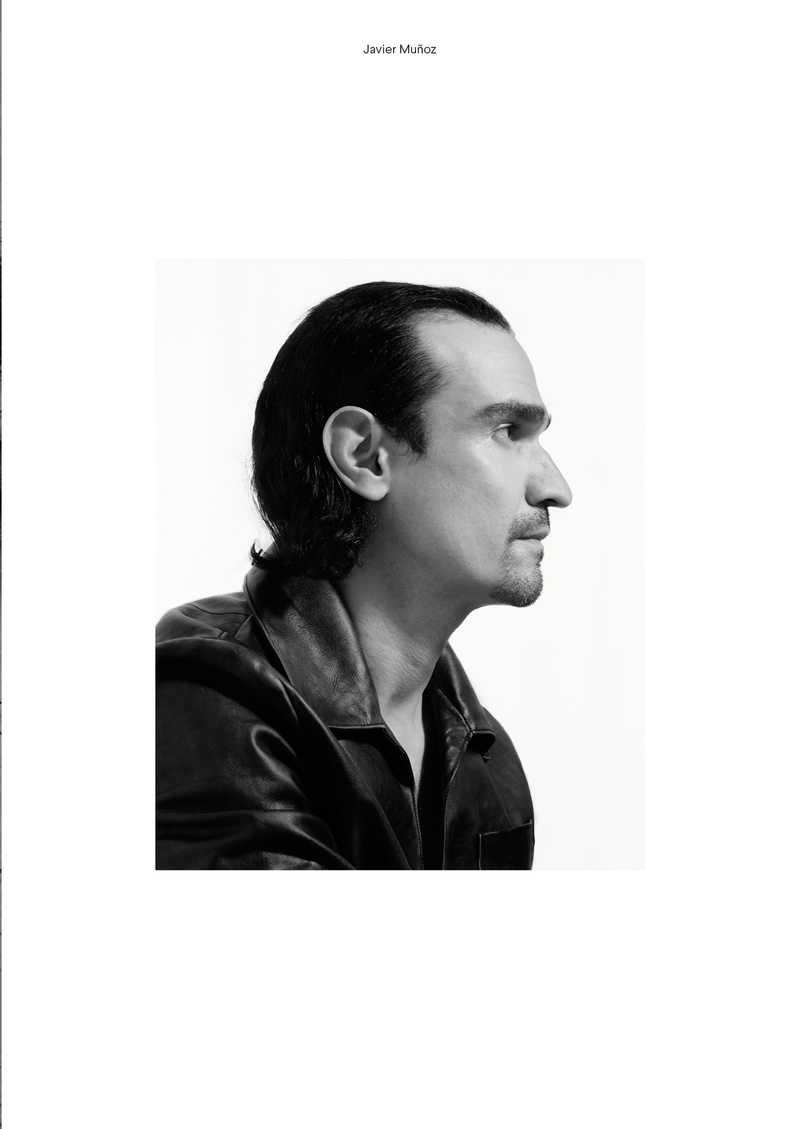

This issue examines the many performances we conduct in our lives, both on and off stage. In one’s work, much of what we do and what we take a stand for is so often for an audience. What’s more important is that what we create has meaning to us, driving us out of bed. As Hanya Yanagihara tells Garth Greenwell: Determination “announces you have something to say.” Stephen Galloway, dancer-choreographer-creative-movement-director, is no stranger to the stage. Where no creative profession is short of obstacles, his had its challenges when it sought to define itself, despite being undefinable. Pressed to take roles that felt tokenistic, even stereotyped, our cover mister, and Hamilton’s leading man, Javier Muñoz saw no point in accepting a gig unless it meant he could do it with his whole self. While working on Hamilton, Javi, who has been HIV positive since 2002, was diagnosed with cancer last year. What pulled him through was the motivation to get back on stage – not for the audience, but for the story. If you’re lucky enough to have your story mean something to someone else, then keep going. Invite them backstage. Let ’em see you.

On Writing a Great, Gay Book

Illustration by Jun Cen

Hanya Yanagihara: I thought lots about what makes a gay book or not. Is it the content, is it who’s writing it, is it the themes, or is it the tone? What is it? Because one of the questions I thought I’d get asked a lot, and didn’t, is: Why are there no Asian-American characters in my book? And are you an Asian-American writer? In the end, I was asked it only twice, both by Asian-American writers, and the answer to both is Yes. I think that much of Asian-American history in America has been, largely for cultural reasons, accepting what’s handed to us. It comes down to a philosophical difference of thinking that life can’t be changed, versus thinking that if you push hard enough against circumstances they will change, which is a very Western way of thinking. There’s a Japanese phrase Shikata ga nai – “It can’t be helped” – and the Eastern way of thinking is simply that. Which is why, for example, people find it perplexing that Japanese-Americans never uprose in large numbers when they were put in internment camps. It simply wasn't part of their philosophy. And in that way, I thought my first book [The People in the Trees] was an indictment of how Asian-Americans have allowed themselves to be treated in this country. I did think that was a very Asian-American book. But no one has called it that, even though I do. So I’m not sure there’s a certain Asian- American aesthetic the way there is definitely a queer aesthetic.

Garth Greenwell: Well part of that may be that Asian-American identity –

HY: You can’t hide it.

GG: You can’t hide it, and also you're born into it, you can’t deny it.

HY: It’s not associated with shame and hiding and a process of discovery.

GG: And education, or initiation. Because I think with gay identity, there’s a kind of initiation to it.

HY: It’s something you have to act upon.

GG: And it’s something you have to seek out. I remember, because I grew up in a very un-gay environment, there were no gay people around me for a long time, and I had to seek out gayness and try to find images of myself that made me not want to die. And that in itself was a kind of training. When I was 13, I went to this bookstore in Louisville that had a lesbian and gay section. I didn’t know anything about literature, I was in Kentucky public schools, and I would just pull books at random.

HY: Do you remember a book you read that you saw yourself in?

GG: I remember Giovanni’s Room, Our Lady of the Flowers, and Confessions of a Mask.

HY: Wow, you really went for the trio.

GG: There’s a way in which, because of that section, I knew that any book I pulled out would speak to me in a way.

HY: There is this idea of the tribe – the emotions are the same, the process is the same. If you are gay, the process of becoming a gay adult is much more similar than not. The circumstances might be different, but the emotions are all the same. And it does cut across nationality and race and so on and so forth.

GG: In that way I could read Mishima and feel that his books were about me. Even though they were books about a world very separate from Kentucky in the early 90s, I could say “This is a book about me.”

HY: What does it mean to write a post-gay novel? If you believe such a thing exists?

GG: I want to hear your answer to that.

HY: I don’t believe it exists. I understand what it means insofar that gay desire isn’t something that has to be written about in code. You don’t have to sort of ferret it out in a book. It’s not subtext, it’s text. I suppose that that could be a definition of a post-gay literary age. But I think “post-gay” assumes that everyone understands and accepts what gayness is. “Post-gay” suggests that gayness is something that isn’t expansive in of and itself, that it’s something that isn’t universal in of itself, that it’s something that has to be moved beyond, and I just don’t think that’s true. What do you think?

GG: The idea of post-gay is bound up in a narrative of gayness and gay community as a response to shame.

HY: Or sex.

GG: Or sex. But if we can get beyond shame then the bonds that might make the identity and the community intelligible will be gone. It’s a kind of wishful thinking that we’ve cleared away all the prejudice and now we can live more expansively, and it’s an understanding of gayness that is far too narrow – it buys into this bogus idea of the universal. The idea of the universal is something that’s scrubbed clean of particularities – all that does is let it be white. All that does is let it be straight.

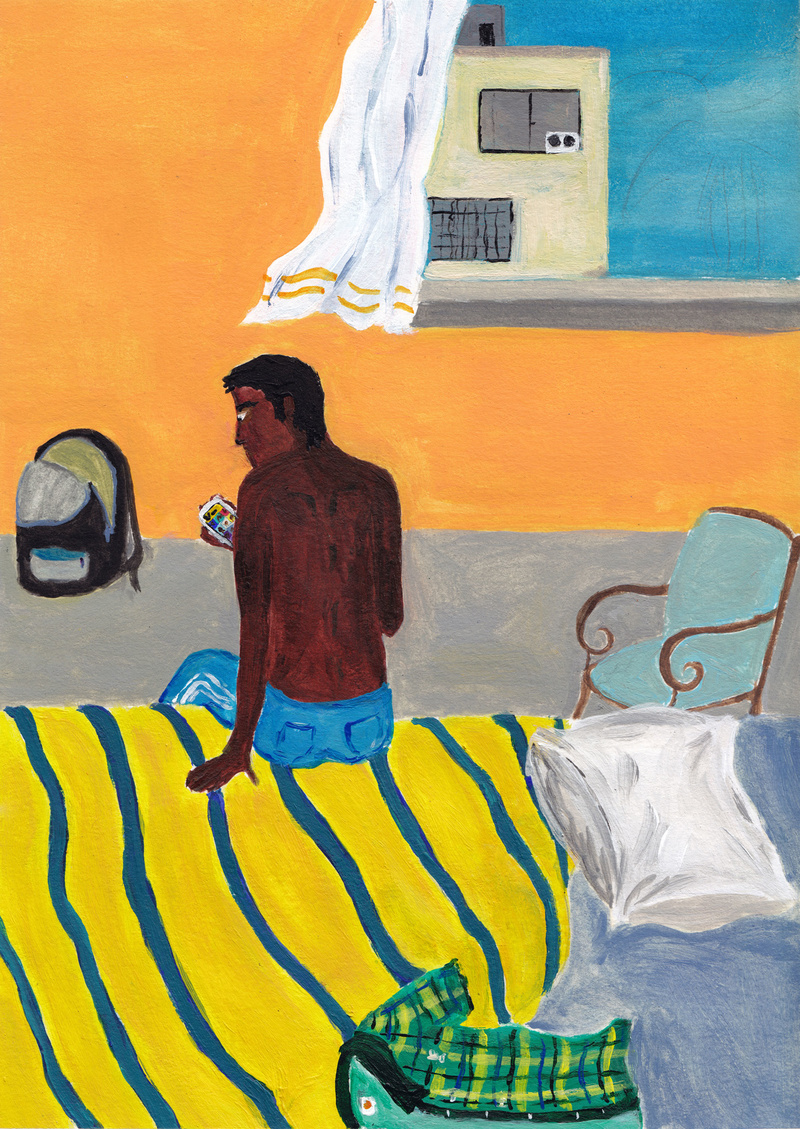

The 21-Year Itch

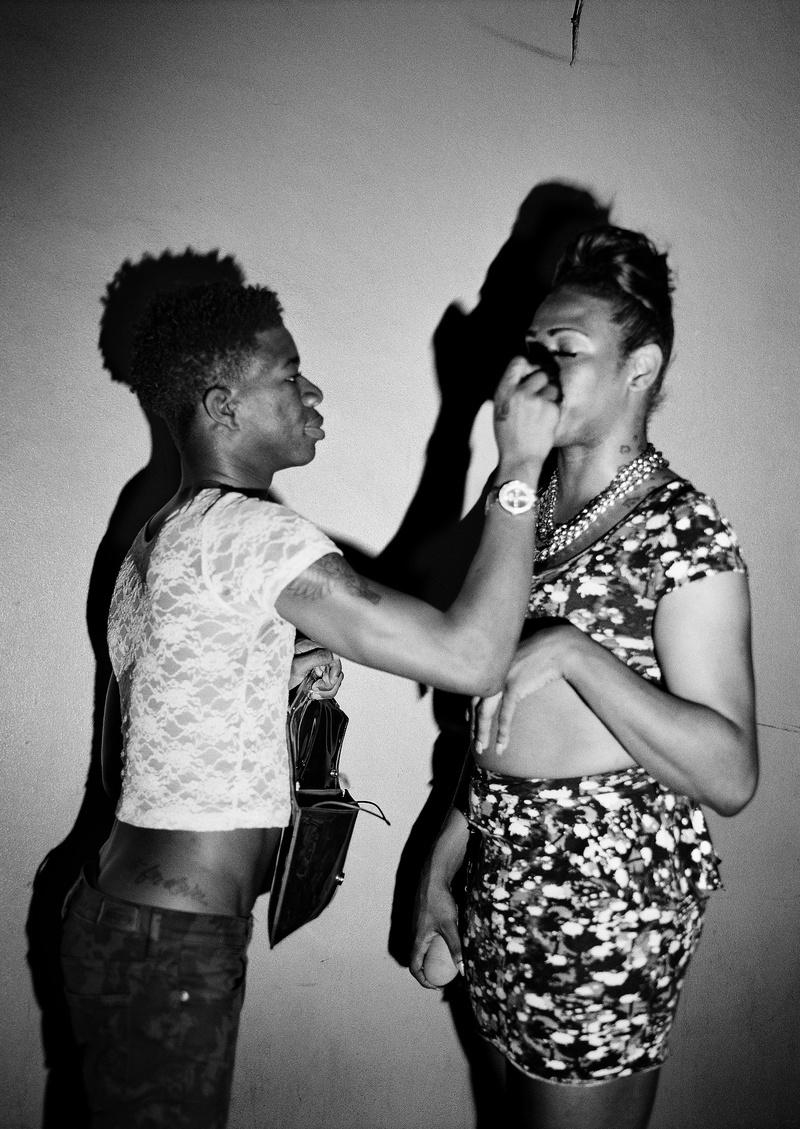

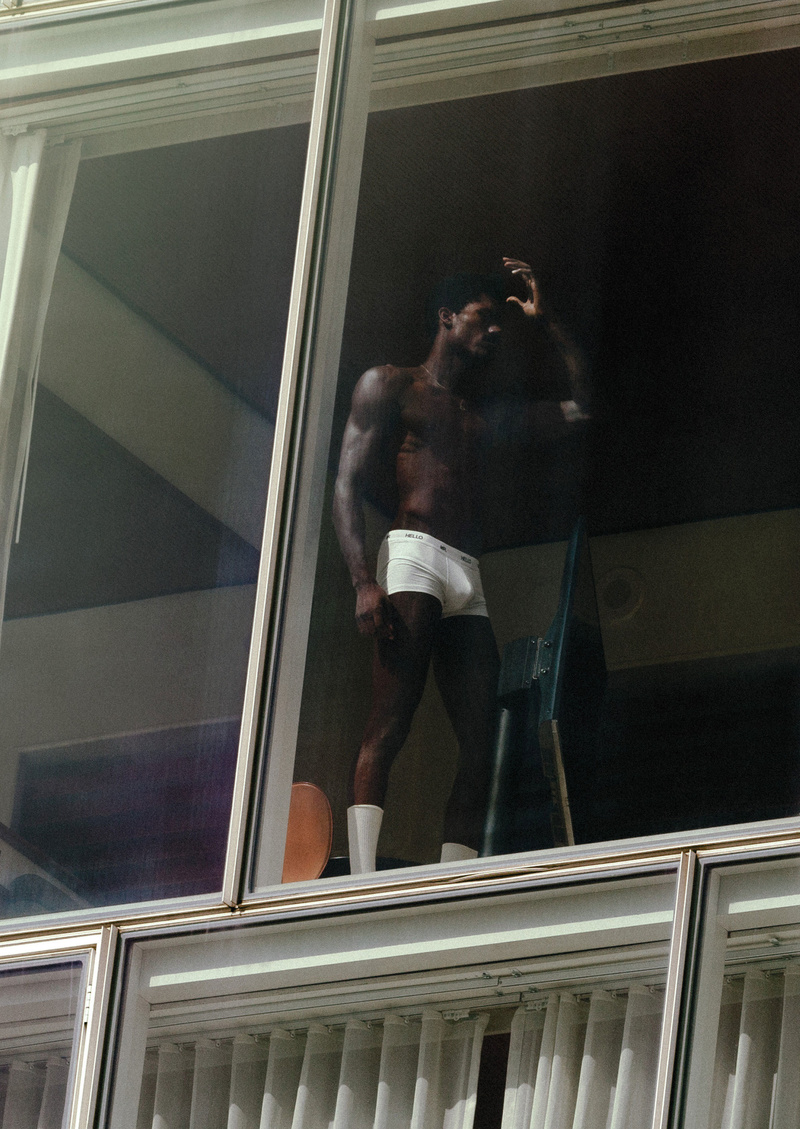

By Harris C., Photography by Colin Roberson

Make no mistake, I have never shied from exerting due effort to be around other queers. Since the first time I left the strictly 21+ gay club scene in Dallas (barring a single scary and sparse college night) and made the 6-hour round trip from my hometown to Austin for Tuezgayz, I was hooked. After years of secretly popping off in front of my sister’s full-length mirror, finding a club with a lazy Tuesday night bouncer changed my life. I was reborn, a sweaty phoenix in a colorful landscape of bodies ranging from corpulent to skeletal, each with their own past, present, and future.

The morning after my first Tuezgayz, I woke up on an air mattress in my friend’s South Austin apartment full of pride, hope, and pure joy. My legs had never been so sore, my sneakers were smudged with a cocktail of spilled drinks, sweat, and mud, and I glowed at the spattering of messages in my phone, “we should hang out.” It was a freedom I had never experienced: to allow my body to move the way it wanted to in public.

I felt radical, revolutionary, inherently political, and I falsely gave all credit to the space itself. The nightclub, I thought, allowed me to dance as I wanted, to create community, and to live my truth. These moments made me realize what the club was, what the bar meant, and what the dance floor could be, and for a time, I fully embraced this ideal. I made the trip down

I-35 as often as my schedule allowed for a free Tuesday night to drive and Wednesday morning to recover, and I will forever be grateful for these formative moments: screaming FKA Twigs lyrics with the first group of gay friends I ever had and mashing faces on the dance floor with boys who saw something captivating in the chunky brown boy in an oversized t-shirt.

But when I came home after that first time, I was yet again reminded of my reality. The peeling plastic of my Oklahoman alter-ego’s ID didn’t prove sufficient evidence that I was of age to anyone in Dallas but a few generous bartenders, and each time a bouncer laughed in my face, I grew increasingly eager for my long anticipated 21st birthday. I hoped and prayed I would stumble upon a similar haven in my own city before then, but in the meantime, I went back to attending parties at my university. I went back to apartments full of engineers and biochem majors, I wouldn’t drink too much, start shaking my ass and betray the leftist intellectual image I so carefully curated for them. I ached for the dance floor, but more than that, I ached to be in a physical space where other people would look at me the way I had started to look at myself: gorgeous, transient, complex. I ached to be seen.