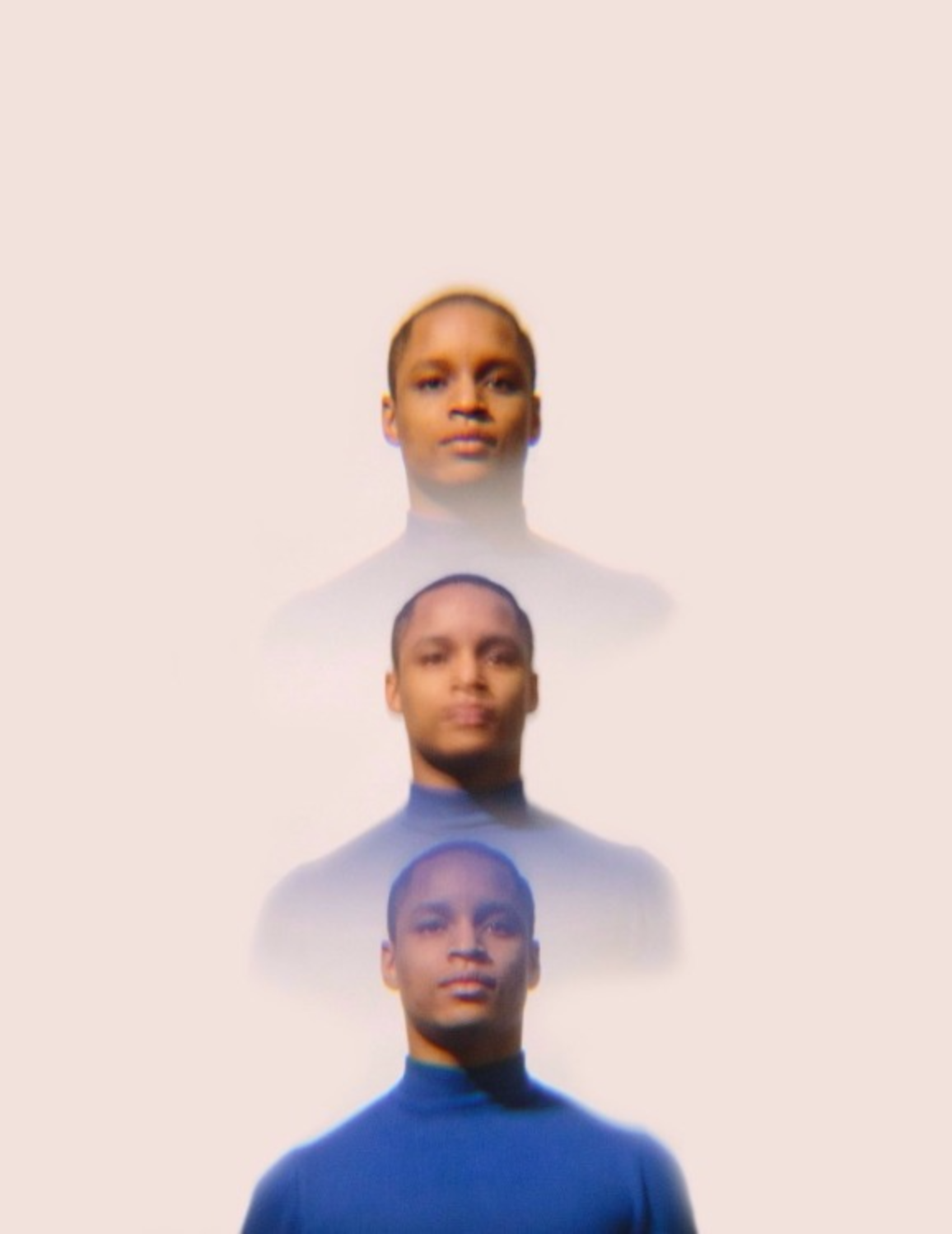

About Face

Text by Scott Bixby

Photography by Chris Schoonover

I can’t remember where I met him exactly, but knowing 21-year-old me, it was probably in the kind of upstate New York dive where you get a free round at the Big Buck Hunter arcade with each pitcher of Utica Club.

I can, however, remember his mouth exactly. Firm, pouty, with rabbit-like

We stumbled back to his dorm room, occasionally ducking behind trees and trashcans to make out, him tugging at my t-shirt as I fumbled with his belt. He had stupidly broad shoulders – hockey, I think? – but I was still searching his face, intuiting from its features the kind of man he was underneath the teen-idol smile. His

The next morning, cotton still tangled between our knees, a late-spring breeze winding through the open window, we lazed into consciousness with sleepy banter, meet-cute pleasantries with an electric undercurrent. While I studied his high, messy eyebrows – little blonde hairs kept catching sunlight at charming angles – I said something about a “conspiracy of silence.” (Probably because I assumed he was

“Like 9/11,” he said with a yawn, tree-trunk arms reclining behind his head.

Hm?

“Oh, yeah,” he said, proceeding to tell me with his perfect mouth all about Tower 7 and controlled demolition and nano-thermite and how if you thought about it the official story was just “too convenient, right?”

Once he got to “no-planers,” I knew that a Round Two wasn’t going to happen.

Slowly, we disentangled our limbs, slipped on underwear we’d cast away and hunted in silence for shoes and wallets. Numbers weren’t exchanged.

How could someone with a smile like that be so stupid? I thought to myself on the walk home.

But who’s the bigger idiot: The guy who thinks Flight 93 was blown up by a government missile or the guy who thinks he can see into someone’s soul through the curve of their lips? It was my drunken stereotyping that had convinced me I’d woken up next to a broad-shouldered poet – deductive reasoning that was clearly no more accurate than his own.

Cut to six years later, when Jon Freeman, director of the Social Cognitive and Neural Sciences Lab at NYU, tells me that my reliance on first impressions wasn’t entirely stupid – or even, necessarily, entirely wrong.

“On emotionally neutral faces, faces that resemble an angry expression tend to be seen as untrustworthy and faces that structurally resemble happy expressions tend to be seen as trustworthy,” Jon told me over coffee. “You can also push this around a bit, in terms of one being neutral: you can kind of upturn the lips and furrow the brows a bit without making an angry expression. We think it’s

Jon studies split-second social perception – that is, how we use facial cues to categorize personality traits and emotions in an instant. His work examines how our brains form spontaneous judgments of other people that can be largely outside our own awareness, to the point that we make judgments about a face’s trustworthiness before we even consciously perceive the face in question.

Basically, Jon has a

“What seems to be a big predictor of perceived trustworthiness is

Jon’s biggest study pinned this subconscious response on the amygdalae, a pair of almond-shaped regions deep inside the brain that process our strongest emotions: Anger, Surprise, Fear, Disgust,

“Facial expression of those emotions has been shown to be culturally universal – you even see it in congenitally blind individuals,” Jon said. They are the emotions that are in our genes.

Prior to the study, Jon – whose sleepy, hooded eyes, high cheekbones, and easy smile put him firmly on the “trustworthy” side of instantaneous categorization – asked volunteers to rate the trustworthiness of a series of faces. The answers were pretty consistent with most other studies on the idea of trustworthy faces: furrowed brows and a downturned mouth are consistently rated as less trustworthy, while higher eyebrows and a higher facial width-to-height ratio are seen as more trustworthy. (Which means that my baby- faced conspiracy theorist, with his wide face and hopeful-looking eyebrows, couldn’t have been a better honeypot if he’d been sent on a secret “Lavender Scare” sex mission.)

Participants were then placed in a brain scanner and shown those categorized faces, but only for 33 milliseconds – about the speed a middle-of- the-pack hummingbird needs to flap its wings once. It was so fast that Jon’s subjects probably couldn’t even be sure that they’d seen a human face, but the amygdalae were already processing the face’s perceived intentions.

“These judgments strongly predict whether or not you want to approach or avoid the individual,” Jon said, down to nudging you into

This subconscious judgment might – Jon stresses the might here – even be accurate. Facial width-to-height ratios aren’t just the result of the universe doodling; they’re related to testosterone. E.g., if you accidentally knock over a guy’s drink at a leather bar (or wherever) and they have a higher facial width-to-height ratio (indicating higher levels of testosterone overall), they’re more likely to put you on a St. Andrew’s Cross.

Jon’s study is made all the more salient by virtue of the ubiquity of selfies. In the epoch of online dating, where three in five gay relationships begin online and split-second evaluations of a guy’s

The ramifications are huge. The casual updating of a Facebook banner, Instagram selfie, or Tinder profile pic may subconsciously tell our friends, followers, fans, and would-be

The more I pored over Jon’s research, the more I started to second-guess not just my immediate attractions or dismissals of one-time flings, but my entire romantic history. Flipping through my mental Rolodex of exes, I picked apart every jawline, every crooked smile, every width-to-height ratio of every face, panicked that I’d trusted my stupid amygdalae over my stupid heart.