Marcus Leatherdale Through the Lens

Text by Martin Belk

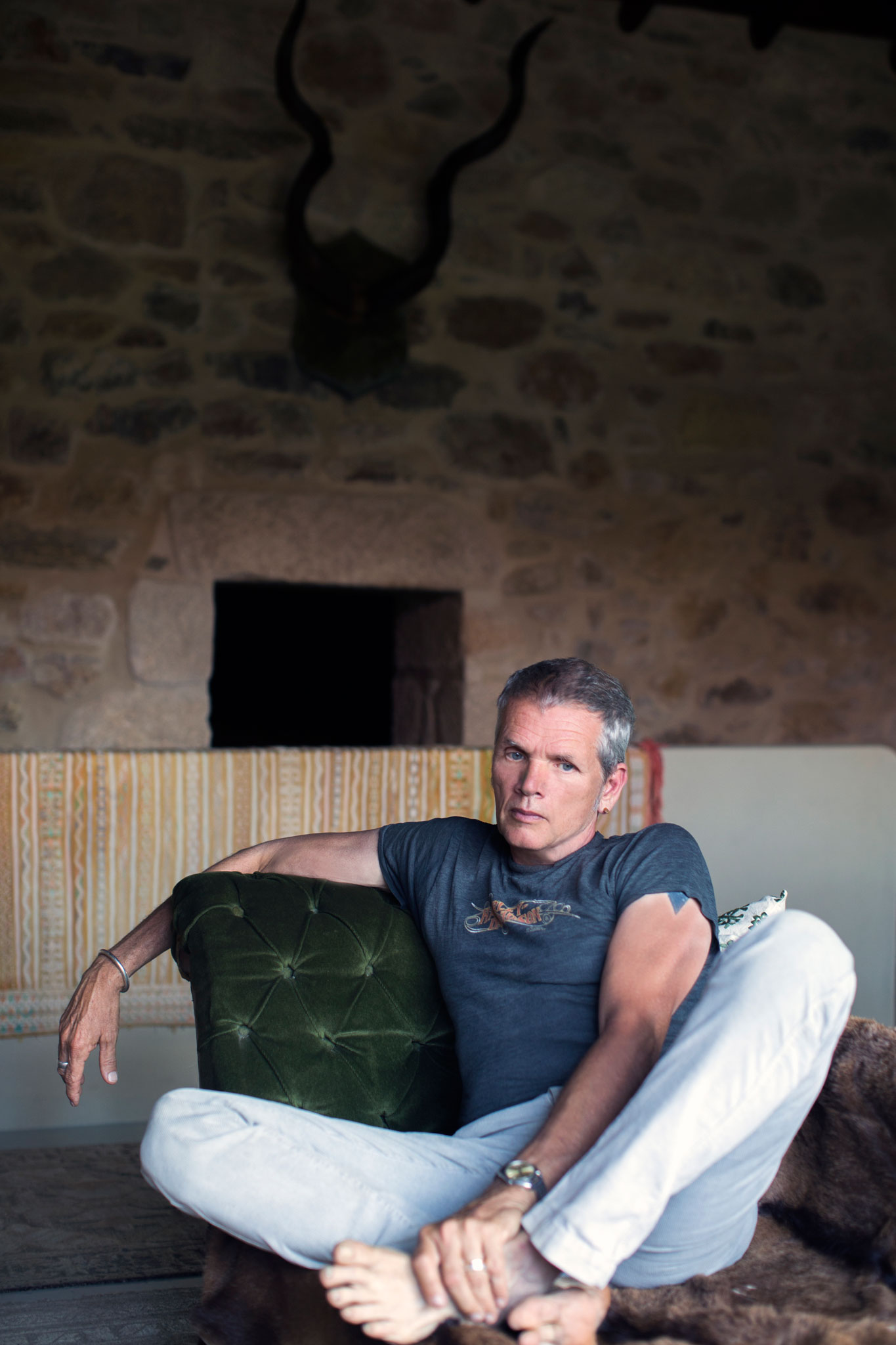

Photography by Jonathan Daniel Pryce

"[Andy Warhol] was one of the first to truly take me and my work seriously. He insisted I sign everything I did, absolutely everything — this really encouraged me. There were lunches at the Factory and dinners out. Andy sat for me several times, and got me work with Interview."

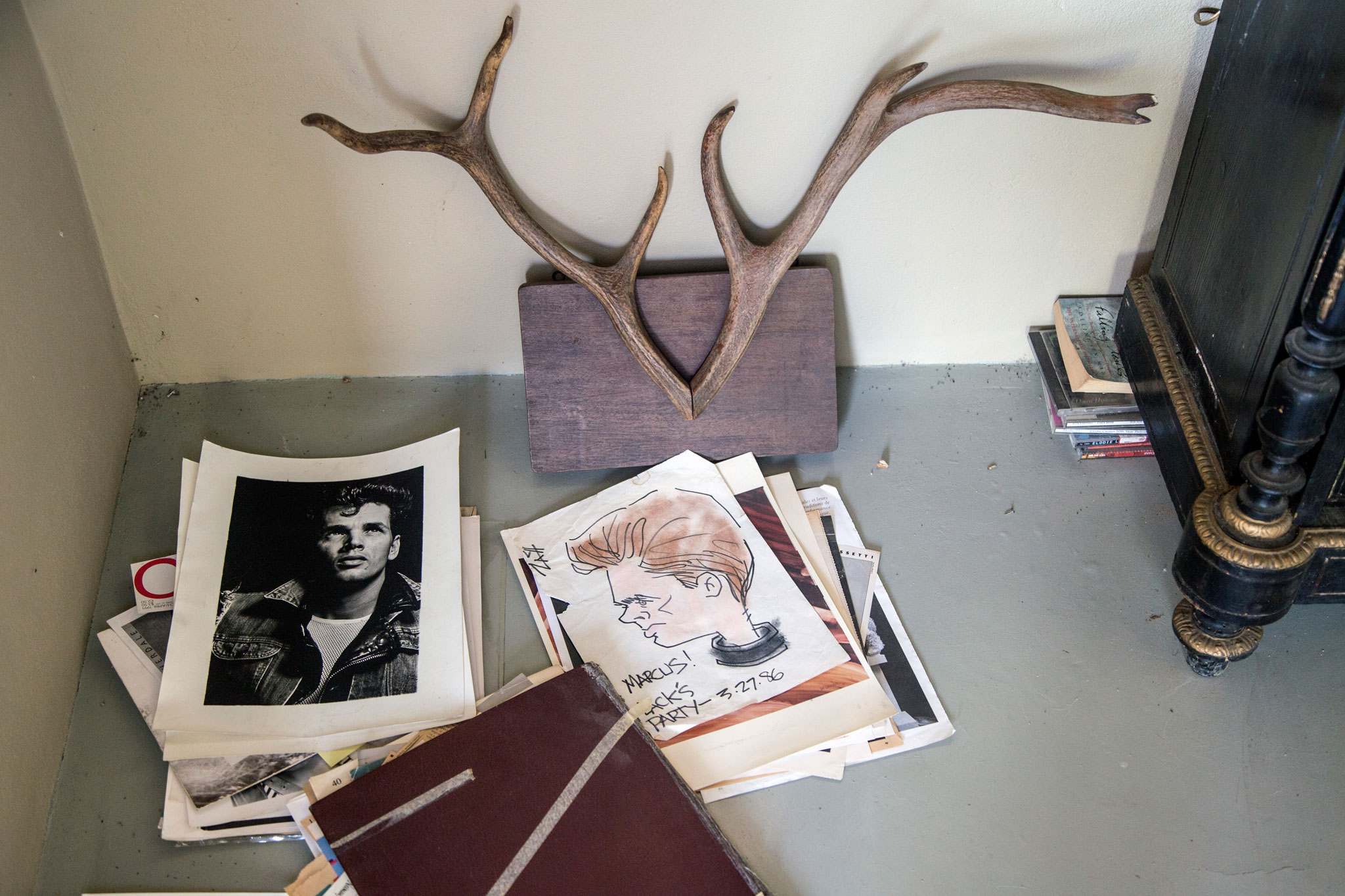

Portugal, July 2015. One by one, the boxes, portfolios, and dusty address books emerge filled with snapshots and fragments of another time. It’s fascinating to observe the ways in which a photographic and creative legacy can inform the present. Images and stories emerge of Jean Michel Basquiat, David Burns, Quentin Crisp, Divine, Keith Haring, Iman, Grace Jones, Liza Minnelli, Issey Miyake, Jack Nicholson, Andy Warhol. The list goes on.

The images and clippings are from the archives of Marcus Leatherdale, a friend for 25 years, who I met on the downtown New York scene — our family of choice. If you use nightlife as a historical marker, it encompasses Studio 54, Area, and Mudd Club through to Pyramid, Roxy, Beige, and Squeezebox! Over the last 10 years we’ve been in conversation about bringing forth his past, making sense of leaving NYC for Europe, as well as his annual sabbatical in India, and what it means to maintain a creative edge in today’s global village.

It occurs to me that looking back is one thing, staring back nostalgically is quite another. Leatherdale’s story is one of connectedness through the creative commune. And, though in recent years the Internet has strengthened and extended the possibilities of this beyond the ghetto, it’s remarkable to realize that shaking hands with Leatherdale, one experiences several degrees of separation to the hands of Tennessee Williams, Christopher Isherwood, and Truman Capote.

As we began to unpack his life on that hot afternoon, some original notions are confirmed: age doesn’t matter, relevance does. Here, Marcus talks to me candidly about some of his most poignant memories so far.

Where did you grow up?

I was born in Montréal, Canada. My father was a veterinary surgeon, my mother a gorgeous housekeeper.

What was it like as a child?

I had wonderful parents. We were privileged and well-off, and I had an absolute terror of an older brother. We moved around a lot, so I was always starting at new schools. School was hell. There was a stretch from 3rd grade to 9th grade where I actually had stability and exactly three friends that I hung out with, which helped a lot. Otherwise, school was absolute hell.

Do you think there’s anything about being bullied – it being hell – that sort of makes you...

...stronger? Like what doesn’t break you makes you stronger? No, I think I could’ve done without it. I don’t think I needed to know how unique and different I was by constantly being bullied for it. I think I could’ve figured that one out without it being smashed in my face. [Laughs] I guess, it did make me stronger, but it got pretty intense – I mean, I was taken out of school for it. I remember my father marching me out of school to a psychiatrist because they were afraid I was going get my ribs broken.

Were you supported creatively growing up?

Absolutely. My father never expected me to be a veterinarian, nor did he encourage me to. My mother used to paint and sing, but she gave all that up – apparently she was on her way to go and become a singer in Europe, but then she met my father. They always assumed I was going to be an artist, and they were very encouraging. I knew I’d go to art school – I didn’t have to fight to not be a lawyer.

And within that, did you always know it was going to be photography?

Ha! No. I didn’t even know what photography was. In 1969 I went to École des Beaux-Arts, as a fine arts major. Within a year the Dean introduced photography, animation and film – so I took a course in each of those. In fact it went from painting forward. With painting I realized I was impressionistic, and didn’t have the skills to do detail – and when I realized detail was a big issue, I thought, “Why in hell should I spend so much time and energy learning to do detail when I can capture it in a photograph?” So I shifted.

Later, in 1977, at the San Francisco Art Institute – where I went for film – I switched to photography, even though I was an honors student as a painter and actually won an award for my painting that year. My teacher, who was himself a successful artist, kept encouraging me to stay and paint, but I didn’t listen and switched over. I still kept a drawing class every day, and I was the only photographer at the Institute that would turn up to photography class covered in charcoal — they just didn’t do both then, but to me it was always as though both were the same thing. So I’ve always approached photography as an alternative artistic medium, not as photography versus art. I never thought of photography as commercial. I never wanted to be a commercial photographer, and didn’t want to work for Newsweek, or be a Playboy photographer. That was not what photography was about for me. Except for Interview, but that was an Andy [Warhol] thing – keeping one foot in fine art, and one in the commercial world.

In that period of time it all sounds so organic and natural. Did you consciously talk about work, creating shoot ideas, or did it just flow?

Nothing was preconceived. This was a time for me when my student fund ran out, and I had to get a job. I first met Robert [Mapplethorpe] at his 1978 show in San Francisco, and through him Sam Wagstaff who had the largest photography collection in the world — and both hired me to manage their studios. I never discussed things with Robert in detail, unless I had to assist him on a rare occasion on location, like when we shot Truman Capote at the United Nations. Working with Sam was amazing. All of a sudden all the slides that were flashing in front of me while I was at University were now sitting in my hands. Images from Irving Penn, Alfred Stieglitz, Richard Avedon. I had to organize them with little filing cards, all placed in a flat drawer — it was a very privileged position.

How did they influence your own work?

It gave me a sophistication — a reference point to where things originated. My inspiration always came from painting and not photography. Although I’ve always loved Sanders and Penn, it was really Rembrant, Caravaggio, and Modigliani that impressed me – their use of light.

A lot of your story is about this incredible world you lived in – the famous people, the places. How did these early experiences change you?

It humanized celebrity. When I met Truman Capote, I had read everything he’d written; and then I met him and he was this sad, little lonely person in a tiny apartment that reeked of hard-boiled eggs. It made things more real and easier for me not to get starstruck. Celebrities can spot an ass-kisser a mile away, and they’ll never become real friends.

Is there a particular memory of New York that really made an impression on you?

I remember one time Yves Saint Laurent threw a party for the launch of Opium on a Peking yacht, and it was sat in a harbor with a long runway. I went with Robert, and I didn’t own a tuxedo; so I went black tie from the waist up, and leather pants from the waist down. I’d also just shaved my head which was unusual at the time. It was amazing – we walked down a runway with rose petals all over the place and ended up hanging out with Paloma Picasso and Saint Laurent. That was impressive. I was a punk then so when everyone started to dance I began to pogo dance. It caught the attention of an artist named Larissa, who became a very close friend. She was head to toe in gold lamé, and gave me my first experience of a limo that night. She took us to Studio 54, and we stayed all night.

And how did Robert Mapplethorpe figure into all this?

Well, while I was in San Francisco, Peter Berlin — another gay icon – introduced me to Robert. And then I got a postcard from him inviting me to New York even though I was already on my way. I house sat his studio while he was away in Amsterdam, and when he returned we became friends. I wasn’t rich. I wasn’t famous. I wasn’t even ‘gay’ at the time, and all the S&M stuff just didn’t interest me. I wore a leather MC jacket to be like Marlon Brando in On the Waterfront, and I didn’t get the other connotations. I guess to some I appeared like packaged meat in the right attire. I never intended to have a sexual relationship with Robert, it just kind of happened as a result of everything else. Robert seemed to only have room in his life for money, fame, and sex — you can figure out which category I fit into.

Was it, as they say nowadays, “complicated”?

Perhaps. But don’t get me wrong, I loved Robert, and still consider him one of my best friends. I could’ve skipped the other stuff and just happily been the best of friends.

What about you and Andy Warhol?

Robert introduced me to Andy initially, but after that, Andy and I became friends. He was one of the first to truly take me and my work seriously. He insisted I sign everything I did, absolutely everything — this really encouraged me. There were lunches at the Factory and dinners out. Andy sat for me several times, and got me work with Interview. I’ll never forget, one night after leaving Mick Jagger’s house for Jerry Hall’s birthday party, we were in a taxi with Tina Chow and were passing a hospital, when Andy looked out and said “I’ll never go into a hospital, because I’ll never get out again.” That was the last time I saw him. Tina died of AIDS not too long after — women got it too. I guess I’m the lone survivor of that cab ride. There were a lot of those back then. The scary thing was that people would be perfectly healthy one minute, gone the next. There’s a photo of me with Andy at the Metropolitan Club with Henry Post, the editor of New York magazine. He was one of the very first in New York City to die of AIDS. That was in the early days when they made you wear a Hazmat suit to go visit and say goodbye to your friends.

Are there any misconceptions about these scenes, the time period, the notorious reputations?

I think the biggest misconception is the myth that people just went out all the time and did drugs constantly — which could be true — but it wasn’t the rule. A lot of these people, myself included, would go out and play for a while but would leave and go back to their studios or apartments and get back to work. There was an incredible amount of hard work, effort and dedication that went into what was one of the most creatively explosive periods New York City has ever seen. This gets missed a lot of the time when people are telling the big party stories.

How did your series for Details, “Hidden Identities” come about?

I was upstairs at the Mudd Club when I ran into Stephen Saban who was then the downtown chronicler for SoHo Weekly News. My first picture ever published was a picture of Mary Lou Green, artistic director of Vidal Sassoon. Stephen had seen it and asked me if I’d like to do some profile photographs to illustrate his weekly articles. It paid $35 a week, or something like that and continued to for about a year until the paper was sold. I still didn’t consider myself a commercial photographer, but later he started Details with Annie Flanders and asked me to contribute. There was a Dada night called “Underground” at that time and I took the gogo cage and made it into a studio for unidentifiable portraits – Dada has always spoken to me. After that, Stephen came to me and suggested “Hidden Identities”. There was an understanding that I didn’t get told who to photograph and when it started there was a sense that if you didn’t know who it was, you weren’t cool enough. As time went on, names would start being revealed in the next issue and eventually the subjects’ names were written in the back of the magazine with more recognizable names like Jodie Foster. It ran from 1982 to 1990. Everyone wanted to be a “hidden identity.” I turned down the likes of Grace Jones because I knew she’d arrive three weeks late – she was notorious for it.

Did anyone in particular stand out for you as a subject?

Leigh Bowery turned up in full drag in the middle of the day. He wore a beaded mask, a bustier, silver boots, and a vagina merkin — butt naked otherwise, in broad daylight. He turned up at my door and I actually never met him without a mask so at the time didn’t even know what he looked like. He couldn’t have been more courteous. After I shot him we left together and went down to Broadway to get him a cab. Two or three went past but one finally stopped. Hailing a cab was lots of fun.

Did anyone not make it into the magazine?

We shot hundreds. Madonna and Debbie Harry didn’t make it in — because Details was sold unexpectedly and became a men’s magazine. It’s too bad, too: there was a lot of funny stuff that happened along the way. When Madonna showed up I put her in my denim vest, and posed her in the lotus position, way before all her yoga, and before I ever started shooting in India — who knew? They’re all in my extended collection now though.

How many frames do you take in a session?

About three to six rolls of 12 per roll. That would just be a warm-up for a digital guy. I use a Hasselblad 500C/M. The only one for professionals.

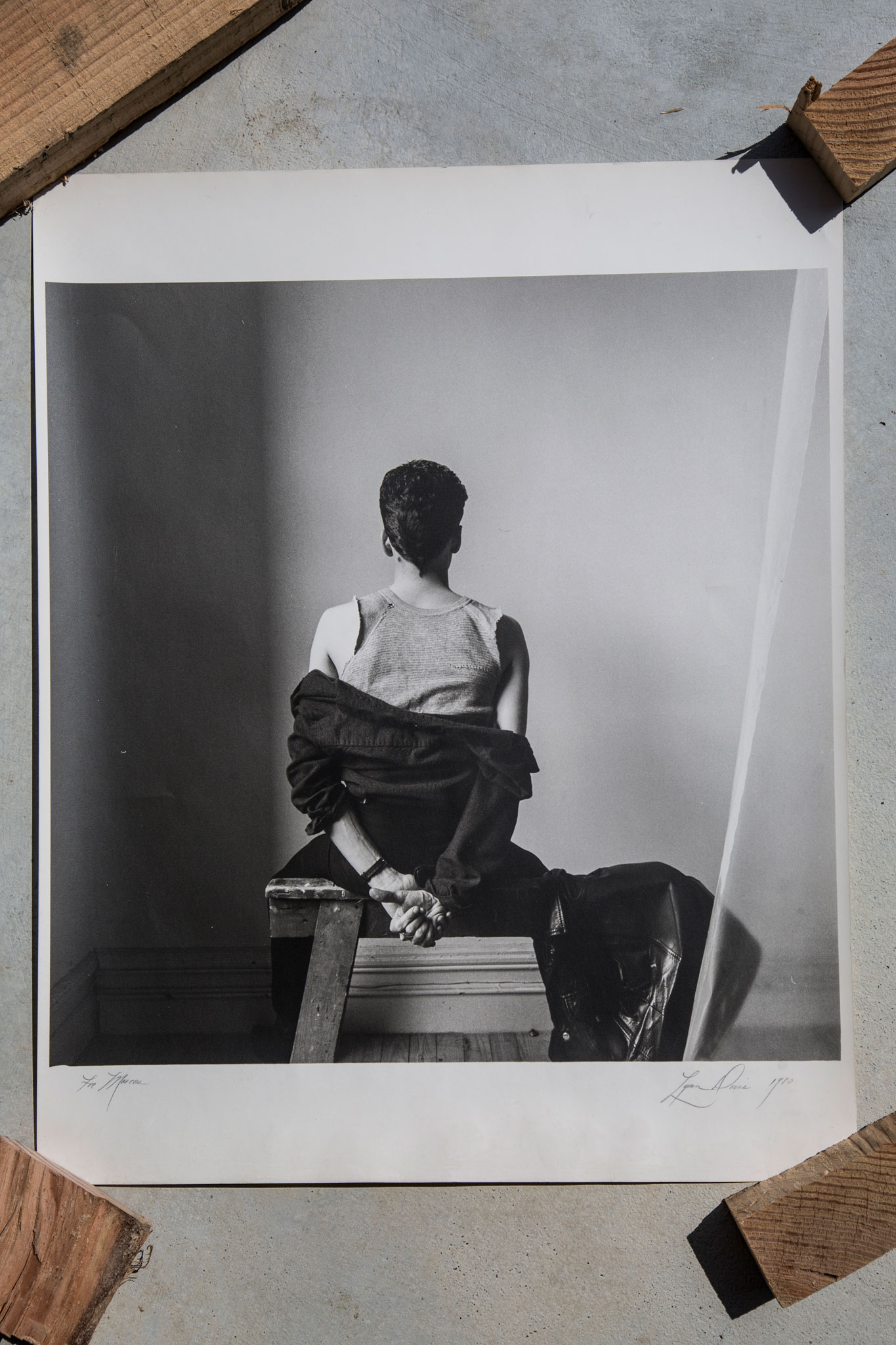

What do you think makes a great photograph?

An internal dialogue. Showing, touching or saying something. It’s art to me. If I had to pick five favorites out of my own portfolio, they would likely not be the famous subjects. It doesn’t have to be who is in the picture.

What do you think makes you skilled as a photographer?

I think the true talent is in the printing. It took me years and years to learn. When I take a photo it’s not just the flash — it’s dodged and burned. I fingerpaint with light. That’s the skill element. Otherwise I’m not interested in wading through the technology to get to the image – that’s just the gesture line in paint. People should just get lost in the image and discover what it says to them.

What did you want to be as a child?

I didn’t have a particular goal. I knew I wanted to be an artist of some sort. I was actually suicidal at 15 because I thought there was no future for me. Luckily my mother had a hunch something was wrong. She left the hairdressers with curlers still in her hair and came home to find me overdosed on sleeping pills. I could never see myself as an adult, but now I’m stuck.

Any words of wisdom?

Enjoy the trip. Enjoy the process. Chances are the destination is not what you’re going to expect — and that’s not a negative thing. I learned that from Robert. He was one of the most discontent people, but one of the most successful. If you live in the past you’ll live in remorse, and if you live in the future you’ll be a worry-wart, so live in the moment. That’s what I’m trying to do.