The 21-Year Itch

Text by H.C.

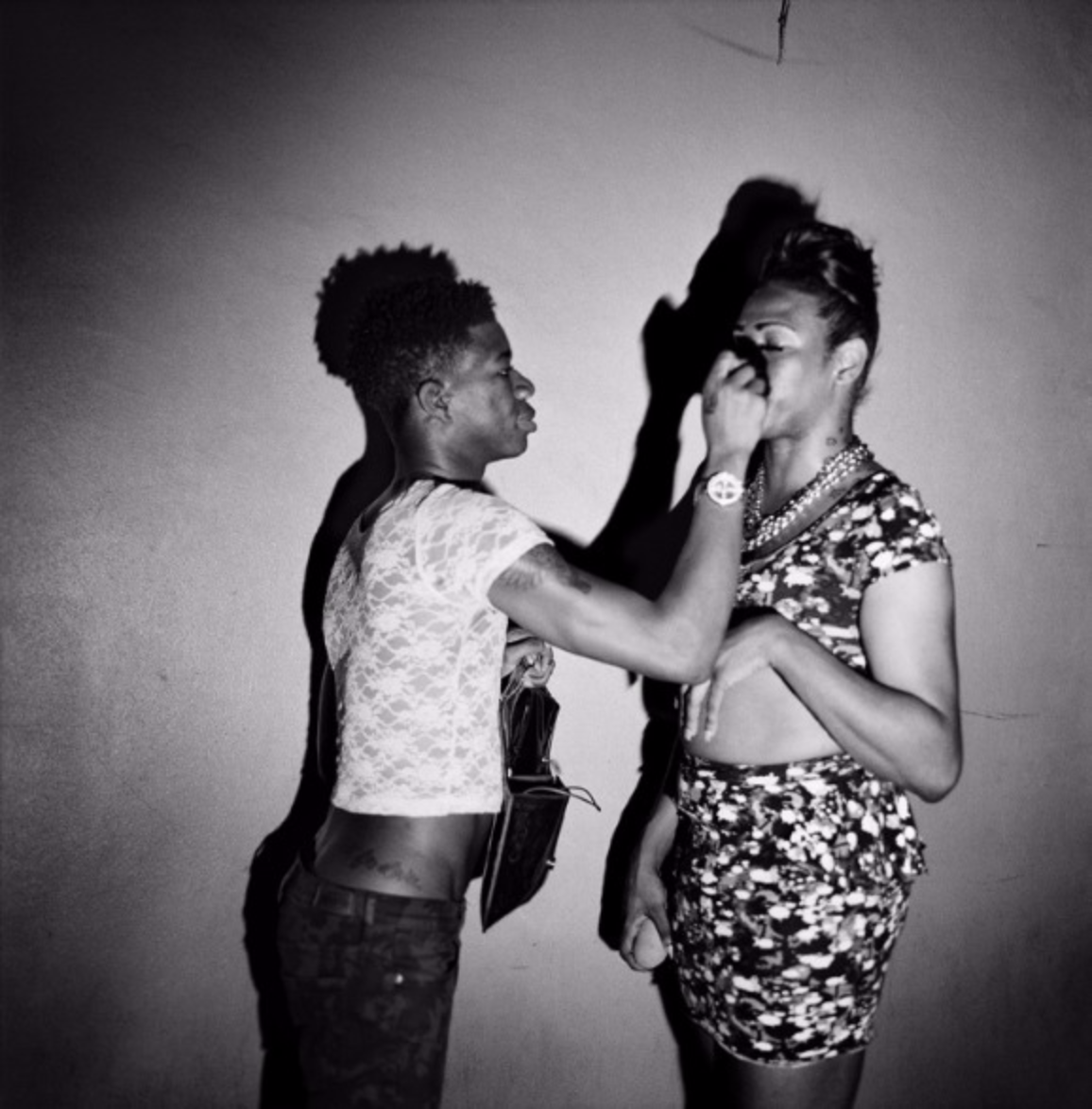

Photography by Colin Roberson

“I love your earring.”

I looked up from my phone. Clammy fingers darted to my ear, running down the length of the single piece of silver dangling from my right lobe I’d debated wearing in public for hours earlier that night. I smiled.

“Thanks so much.”

“Thanks so much.”

He brushed a hand on my shoulder, angling his body away from the door.

“Of course, babe. Where’s it from?”

I’d bought it in Spain, I said, but as soon as I hinted that I spoke Spanish, his thick Colombian accent went from zero to sixty as he switched to his preferred tongue. Shifting from a sharp and purposeful English to a sweetly flowing Spanish, he told me his parents moved to the US from Colombia and Ecuador 25 years ago. I told

“My tongue is very liquid tonight,” I said, and he giggled. He heard Santigold playing inside and his eyes lit up. “Are you coming back in?”

He touched my hand and said something – it was probably really cute, but I was too busy staring at his jaw to remember – and suddenly all 6’1” of his dark, toned body floated past the bouncer and through the tiny door, glancing back with a smile, his skirt bobbing side to side.

Outside, every outfit waiting in line looked like it was pulled from a magazine or off one of the Instagram models whose lives I knew better than my own. Straight-cut denim on smooth legs longer than half my body gave a starched structure and balance to cropped tanks. Bandanas

My heart thumped to the bubblegum beat pouring out of the building as I watched others follow in ritual procession. As their turn came, they either flashed an ID, gave a name on the guest list, or had a friend come grab them before passing the hallowed velvet ropes. Most paid the $12 cover, but for some, making the bouncer bend to their charm seemed almost a sport. I had $15 in cash but my glaringly obvious fake ID was burning a hole in my pocket, not to mention that my only friend inside was too busy working to get me in, and I definitely wasn’t important enough to be on the guest list. I stood, waited, and watched as satin, lace, silver, and gold traipsed their way through the door.

I had only landed in New York three and a half hours earlier, on a flight booked just five days before. Fueled by nothing more than limited experiences with queer nightlife and some intuition, I bit the bullet and paid the airline fee to move my flight time, arriving in the city just in time to drop off my bags, put on a cuter outfit, and get to Brooklyn for a Facebook invite that seemed too good to miss. The entire sequence was almost romantic, like life’s loving embrace was telling me to attend this party. I simply had to go. It was the third anniversary of Papi Juice, headlined by two of my favorite artists, and it was on the very weekend I was set to arrive in New York for the summer. It was meant to be.

Make no mistake, I have never shied from exerting due effort to be around other queers. Since the first time I left the strictly 21+ gay club scene in Dallas (barring a single scary and sparse college night) and made the 6-hour round trip from my hometown to Austin for Tuezgayz, I was hooked. After years of secretly popping off in front of my sister’s full-length mirror, finding a club with a lazy Tuesday night bouncer changed my life. I was reborn, a sweaty

The morning after my first Tuezgayz, I woke up on an air mattress in my friend’s South Austin apartment full of pride, hope, and pure joy. My legs had never been so sore, my sneakers were smudged with a cocktail of spilled drinks, sweat, and mud, and I glowed at the spattering of messages in my phone, we should hang out. It was a freedom I had never experienced: to allow my body to move the way it wanted to in public.

I felt radical, revolutionary, inherently political, and I falsely gave all credit to

But when I came home after that first time, I was yet again reminded of my reality. The peeling plastic of my Oklahoman alter-ego’s ID didn’t prove sufficient evidence that I was of age to anyone in Dallas but a few generous bartenders, and each time a bouncer laughed in my face, I grew increasingly eager for my

But where my nights at Tuezgayz were formative, they soured when I had my virginal confrontation with a threat that’s now become a near-constant in my life. After an hour of standing guard over my friends’ drinks as they hit it off with dancefloor suitors one after another, I lobbed a drunken grin to a white guy with a nice beard, and he set me straight with a slurred “I don’t like browns.” He made his way back across the dance floor, and as I watched him laughing with his friends, I started to tear up. Not because of him in particular, but because in that moment, my image of “going out,” as gay celebrities, leaders, and icons had helped me imagine it, was shattered. After years of cold, one-sided online interactions with men who wanted nothing to do with my complexion, it finally happened in person, and my confusion, my shock, and my bubbling anger slowly transformed into relief. It was as if once the wool of $3 vodka Red Bulls and hourly drag shows had been pulled from my eyes, I could see it all. All the times I had seen Facebook posts about complicated relationships with alcoholism and nightlife, heard friends’ haunting stories about sexual assault in club bathrooms, read articles pleading with bars to stop profiting off queer nights without stopping the violence creeping out of the peripheries. As soon as I could no longer perform what I had been told was an avenue to liberation, to community, and to an alternative family, I was, in a sense, freed.

I slowly realized that no matter how old I was, no matter how good my fake ID was, and no matter how many bouncers I could slip by, these spaces would never be safe for me and for most of my friends. I began to realize that the longer I continued to search for satisfaction and for meaningful interaction in these spaces, the longer I would be disappointed, dejected, and lonely. But where was I to go otherwise?

While alternative and community-created spaces can be more inclusive toward younger folks, people of color, and many other communities, they are absent where they are needed most. With the rapid brain-drain of queer artists, activists, and thinkers in the South, I am left a queer teenager in North Texas, with nothing to do but cruise dating apps and chat rooms for hours upon hours, sitting in my bedroom refreshing my phone with a ghostly concentration, hoping to find someone within a reasonable radius to just appreciate me. Beyond that, the only institutional presences of queer culture I know of are health centers and nightclubs, and I’m not exactly sure how to go about making friends over STI tests. My placelessness has only been intensified since I attended New York Pride this summer. A celebration heavy with the weight of post-Orlando grief, punctuated by tributes, memorials, and remembrances, the parade somehow still managed to wash away the real political meanings that underscore the tragedy, tucking them away within the folds of Bank of America rainbow flags, a glitzy NYPD squad car, and a flood of beads and flyers shrieking homonationalism. Without a space to call my own, this is what I must return to.

If you’re not 21, liberation is not for you. If you’re not 21, you should go somewhere else. If you’re not 21, you need to wait your turn.

The funny thing is, I have been waiting. I’ve spent the better half of my 19 years on this earth waiting my turn. My white peers, teachers, and mentors have told me I should be happy with

So when people tell me to wait my turn, excuse me if I laugh, but I know this waiting room all too well. Excuse me if the safe spaces you’ve sent me to weren’t safe at all.

But, as I wait, I cling to the moments of freedom I do have. Breaking my Ramadan fast in a Harlem apartment with defrosted lamb korma alongside a table of queer and

And it is with these moments I question the vision for the future I am presented with on a near daily basis. More moments like these would create a fantastic queer future for us and our siblings, a future centered around artistic and intellectual creation, community, and articulations of mutual appreciation beyond nightlife. Progress has been made, but I still sit in the margins, waiting for my turn as we move toward a future that is constantly seeking to do better. And though I know it's futile, the piece of me that just wants to dance will never die, so I still stand in lines on Saturday nights, hoping I'll find an easy bouncer, a back door, and a place to feel free.

The girls I had been standing next to for the better half of 90 minutes were chatting about how sad it was to see so many good outfits being turned away at the door, a waste of hours of thought, thrifting, and threading. I matched their frustration with an exasperated nod and we talked for a minute about how rude the bouncer was

She squinted and asked me to say it again. Laughing at my attempts to even recall the same number, she flicked the card in my direction and shooed me away to the sound of my feeble protests.

"It – it’s my parents’ house. They moved.” •