We’ve been taught to believe we deserve nothing but the best in life. “Never settle” is the mantra of our generation and it no longer seems crazy to think that we can change the world. This issue is for those who challenge the ideals of others. Our seventh cover boy, Parson James, is consumed by his drive and push for something beyond where he came from. For him, “impossible” was never an option. Our studio visit with the artist duo Elmgreen & Dragset shows us a new level of precision – the changing of a color, the texture of a material. In their case, dissatisfaction continues to work to a great advantage. We seek more meaningful answers in our relationships and in our work to collect evidence that we are constantly moving forward, proving to others, but more importantly to ourselves, that we can always do better.

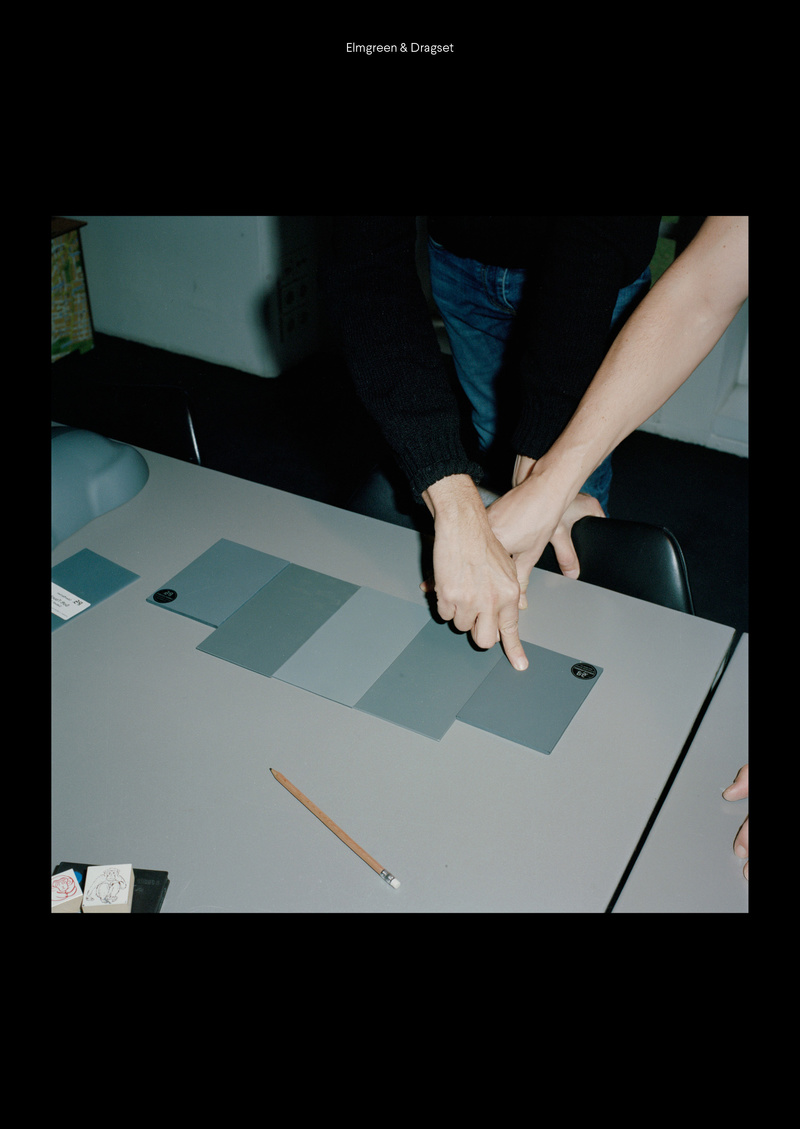

Elmgreen & Dragset

Photography by Mark Peckmezian

Subversive, but never without a sense of humor, artist duo Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset have been questioning the status quo of the contemporary art world with their site-specific installations for the past 20 years. The pair first spotted each other as the only guys sporting post-punk haircuts and Doc Martens at Copenhagen’s popular club After Dark back in 1994. After hitting it off, and realizing somewhat fatefully that they both lived in the same building, they soon became a couple and started experimenting with performance art.

Now based between Berlin and London, the two have since broadened the meaning and use of traditional artistic mediums. Their work, found in prominent public spaces, aims to challenge—like Powerless Structures, Fig. 101 in London’s Trafalgar Square, featuring a golden child on a toy horse, or the eerie, glistening Han in Copenhagen. Their obsessions revolve around gender, adulthood, and identity but, at the same time, appear purely superficial, banal, and fun. It is, however, their more conceptual work that really captures the imagination of the art world. They have a knack for redefining the genre – take Too Late, which saw an entire London gallery converted into a gay club, complete with after-hours ephemera. And Prada Marfa, an entire Prada boutique complete with authentic shoes and handbags selected by Miuccia herself, installed in the middle of the Texan desert – now an Instagram omnipresence. More often than not, the viewer’s gaze is redirected inward, just as Michael and Ingar push their own boundaries in self-reflection.

Elmgreen and Dragset, "the artist duo," create exhibitions that neither could have done without the other. After more than 20 years of collaboration, the pair is no longer romantically involved, but they continue making art together, reinterpreting what it means to be a man in both their body of work and their personal lives. addressing sociocultural themes with enormity and a wink.

Although their similarities brought them together, it’s their differing ideas that make their installations so conflicting and enduring, a quality you’re able to understand if you spend a day with them. In this issue, we spend a typical day with Michael and Ingar, though you’ll agree, it is anything but typical.

About Face

Excerpt by Scott Bixby

Photo by Chris Schoonover

Jon Freeman studies split-second social perception – that is, how we use facial cues to categorize personality traits and emotions in an instant. His work examines how our brains form spontaneous judgments of other people that can be largely outside our own awareness, to the point that we make judgments about a face’s trustworthiness before we even consciously perceive the face in question.

“What seems to be a big predictor of perceived trustworthiness is structural resemblance to emotional expression,” Jon said. “We all have our resting face, the physical constraints of our musculoskeletal makeup. Some people have ‘resting bitch face,’ some people have baby-faced features... Overall, faces that have sort of resting bitch face in terms of the angry side or the untrustworthy side are subconsciously deemed untrustworthy.”

Jon’s biggest study pinned this subconscious response on the amygdalae, a pair of almond-shaped regions deep inside the brain that process our strongest emotions: Anger, Surprise, Fear, Disgust, Joy and Sadness.

“Facial expression of those emotions has been shown to be culturally universal – you even see it in congenitally blind individuals,” Jon said. They are the emotions that are in our genes.

Prior to the study, Jon – whose sleepy, hooded eyes, high cheekbones, and easy smile put him firmly on the “trustworthy” side of instantaneous categorization – asked volunteers to rate the trustworthiness of a series of faces. The answers were pretty consistent with most other studies on the idea of trustworthy faces: furrowed brows and a downturned mouth are consistently rated as less trustworthy, while higher eyebrows and a higher facial width-to-height ratio are seen as more trustworthy. (Which means that my baby-faced conspiracy theorist, with his wide face and hopeful-looking eyebrows, couldn’t have been a better honeypot if he’d been sent on a secret “Lavender Scare” sex mission.)

Participants were then placed in a brain scanner and shown those categorized faces, but only for 33 milliseconds – about the speed a middle-of-the-pack hummingbird needs to flap its wings once. It was so fast that Jon’s subjects probably couldn’t even be sure that they’d seen a human face, but the amygdalae were already processing the face’s perceived intentions.

“These judgments strongly predict whether or not you want to approach or avoid the individual,” Jon said, down to nudging you into unconsciously unfriendly body language (crossed arms) or a more welcoming posture. (Let your imagination determine what that means.) “It even predicts people’s willingness to actually trust other people with money.”

This subconscious judgment might – Jon stresses the might here – even be accurate. Facial width-to-height ratios aren’t just the result of the universe doodling; they’re related to testosterone. E.g., if you accidentally knock over a guy’s drink at a leather bar (or wherever) and they have a higher facial width-to-height ratio (indicating higher levels of testosterone overall), they’re more likely to put you on a St. Andrew’s Cross.

Jon’s study is made all the more salient by virtue of the ubiquity of selfies. In the epoch of online dating, where three in five gay relationships begin online and split-second evaluations of a guy’s dateability are only a swipe right (or left) away, Jon’s research sounds like it confirms what we’ve all secretly worried about: that we’re being judged before we even open our mouths – before we’re even consciously perceived.

Geography Lesson

Excerpt and photo by Tag Christof

Legend had it my biological father was a handsome, artistic Spaniard. He was a painter or musician or something equally mysterious, and he disappeared without a trace well before I was born. By the time I was a toddler, my mother had entered into a marriage of convenience – a sad Brady Bunch of tidier symmetry: He had a daughter, she had me, together they had my brother. He legally adopted me, I inherited his generic English name, and the family fairytale limped along through a half-decade of his abuse, affairs, and alcoholism. They divorced at last, following a spectacular confrontation after my mother braved an affair of her own. We hid out for days in a motel room just off the interstate, my mother, my brother, the illicit boyfriend, and I. Our car was stolen the first night, but at least we were safe. I was proud of my mother. It wasn't long before that relationship also went up in violent flames, but she was free. We were free.

Despite my protests, my mother and grandparents decided it was best I keep that easy-to-pronounce adopted name, mostly because it will open doors in the world for you, mijo. But I was already white enough to reap any advantage a name might bring. Just as I was already way too white to avoid bullying at school for looking like the people our families told us to hate. Privilege is relative.

I learned to beat off thinking about the rough boys with crew cuts and black slicked-back hair who had their run of the school. The ones who were good at football and knew about Hip-hop. They despised me, so I retreated into band class and art class and anywhere else they weren’t. I made out with girlfriends I hated making out with while I longed for those badasses – the same ones who slashed the tires on my first car. The same ones who used shoe white to scrawl “white fuck” and “dirty gringo” on its windows and on cafeteria walls. Next to those, faggot and joto barely registered. I knew they didn’t really know, anyway. They called everyone faggot. They seemed to say, you can be a faggot and still be mostly like me. You can be a faggot and still be my primo or my hermano or my friend. I don’t care who your family is, you are none of those things if you are a gringo.

In college, I learned French and spit-shined my Spanish. I adopted an inscrutable new name, invented mostly out of thin air, to sound as plausibly Swiss-generic as American-cosmopolitan. And then I escaped America altogether, first to France, then to Italy, then England. Far away, I was from somewhere only vaguely real: the storied land of Santa Fe with its Georgia O’Keeffe overtones and cerulean skies. Privilege is reinvention. Privilege is a twenties spent having my heart broken by Italian royalty, a debonair French architect, a British film director, a moody Irish musician whose beautiful name I had tattooed on my leg in a moment of desperation.