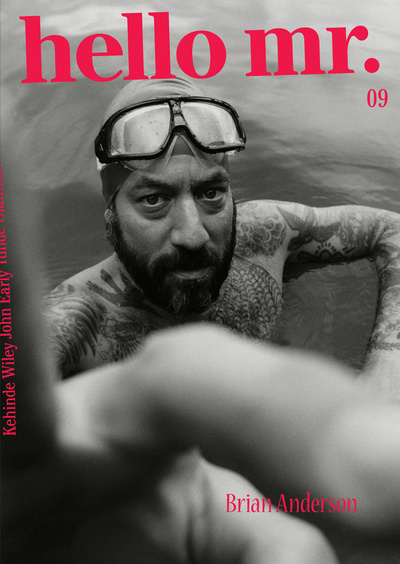

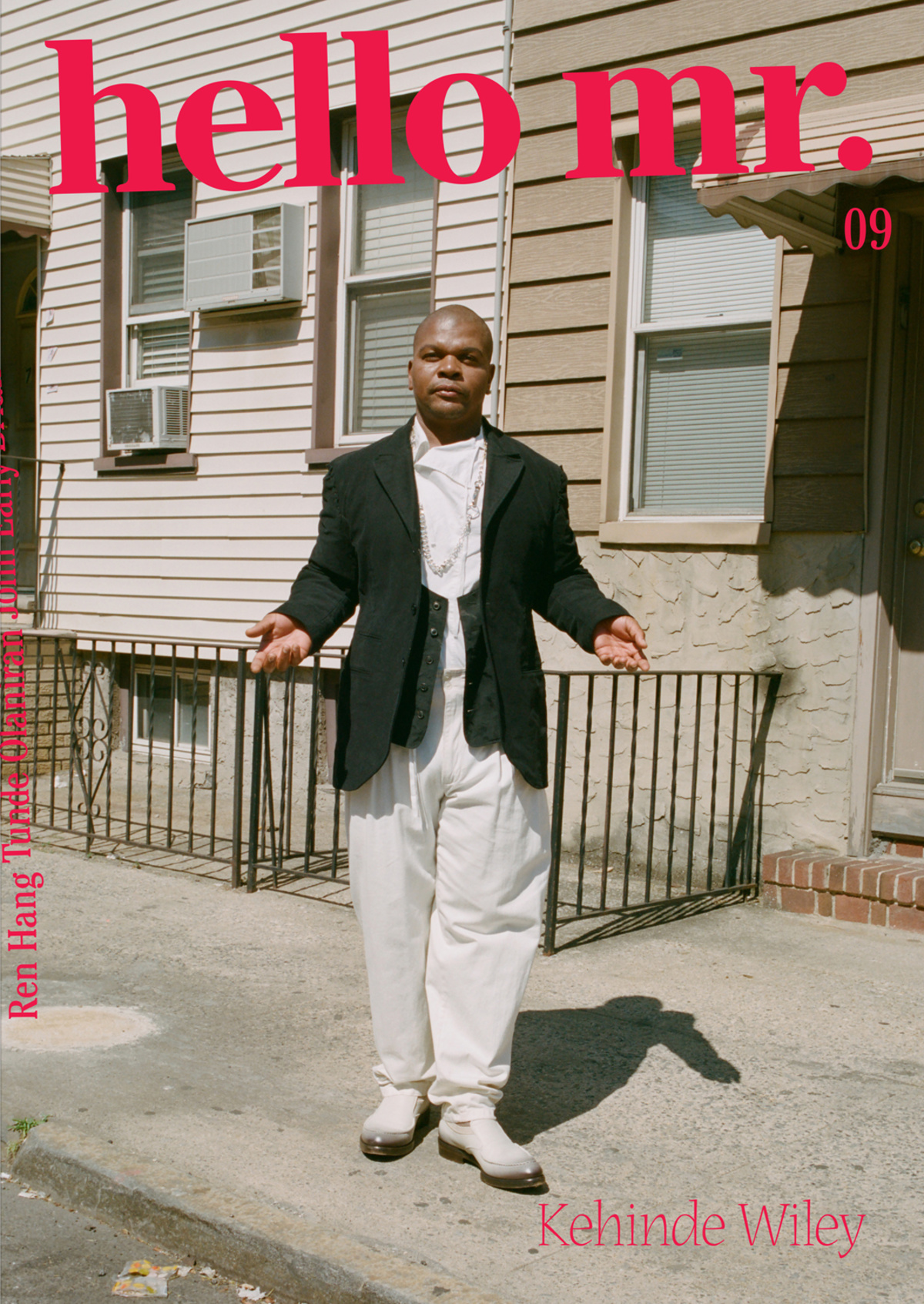

So many of the most powerful cultural forms are the product of turmoil, heartbreak, or pain. In one of our three cover stories, artist Kehinde Wiley teaches us not to fear anxiety: “Roll it around in your hand, and try it on for size... that’s your guiding light.” Finding the courage to discover this light allows us to guide others. Brian Anderson, the professional skateboarder who came out publicly last year, has reinvented himself by getting intimate with that fear. John Early reminds us how when things get really bad, like current-political-climate-bad, sometimes the best thing to do is laugh.

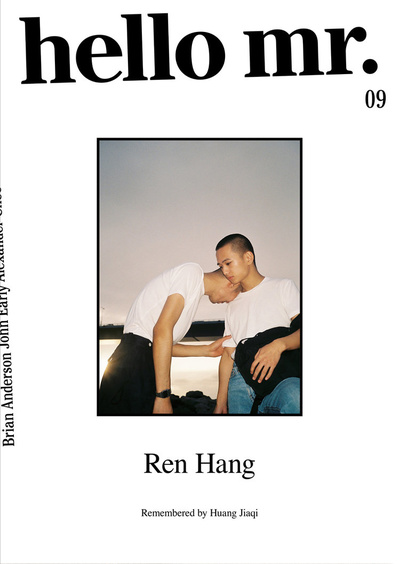

We know all too well that artists are held by this cultural standard because we are counted on, if not required, to be emotional, to be vulnerable, to be empathetic. As Jenna Wortham, co-host of The New York Times podcast Still Processing says in this issue, the work of a culture-convenor is to pursue answers and take emotional leaps to pave a way forward for all. And finally, Huang Jiaqi, boyfriend of the late photographer Ren Hang, opens up in his first interview about their relationship, Ren’s turmoil, and the legacy of his work.

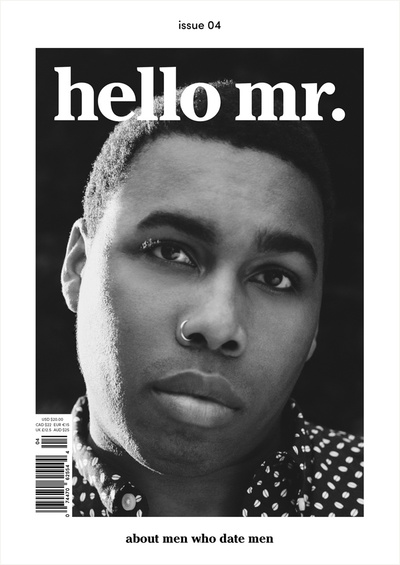

Text by

Antwuan Sargent

Photography by Amber Mahoney

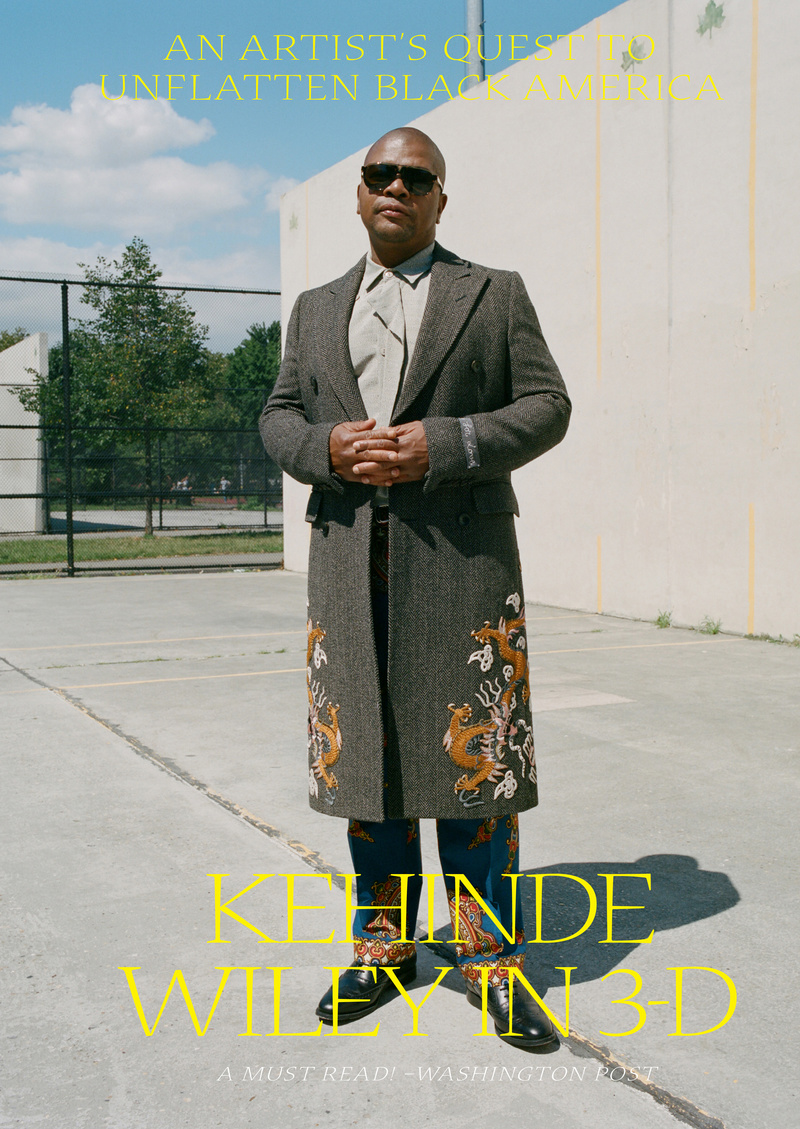

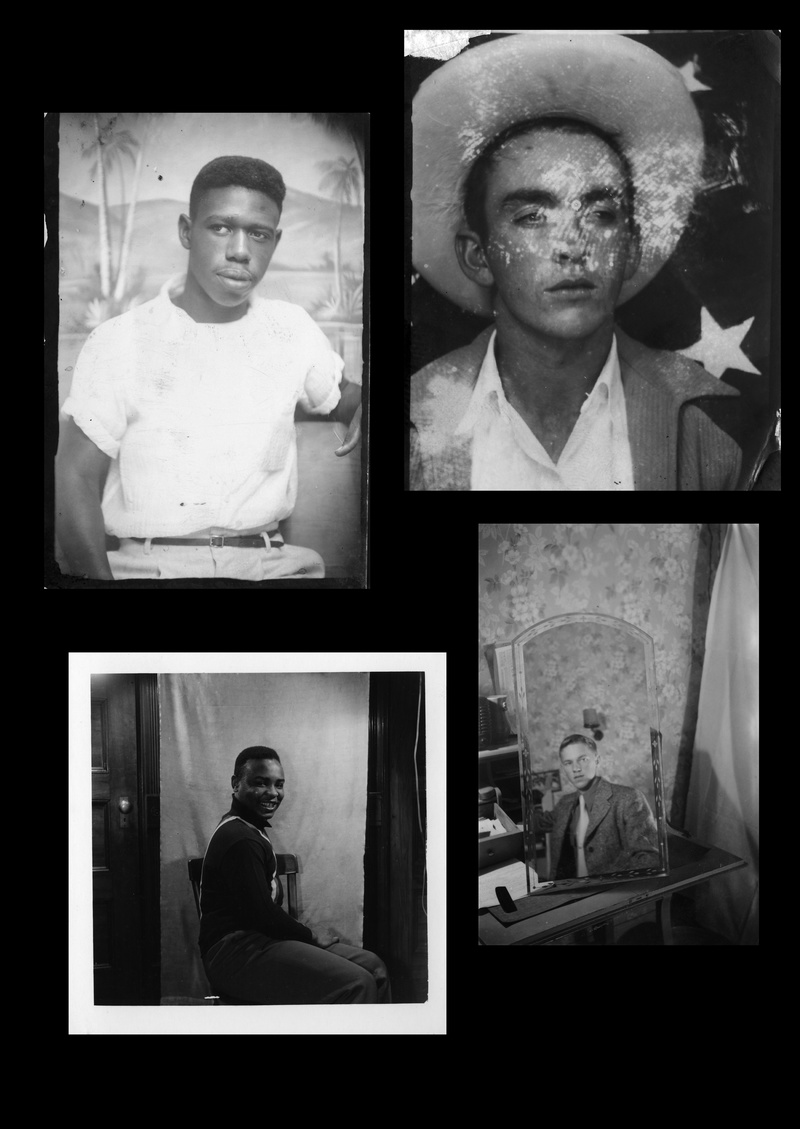

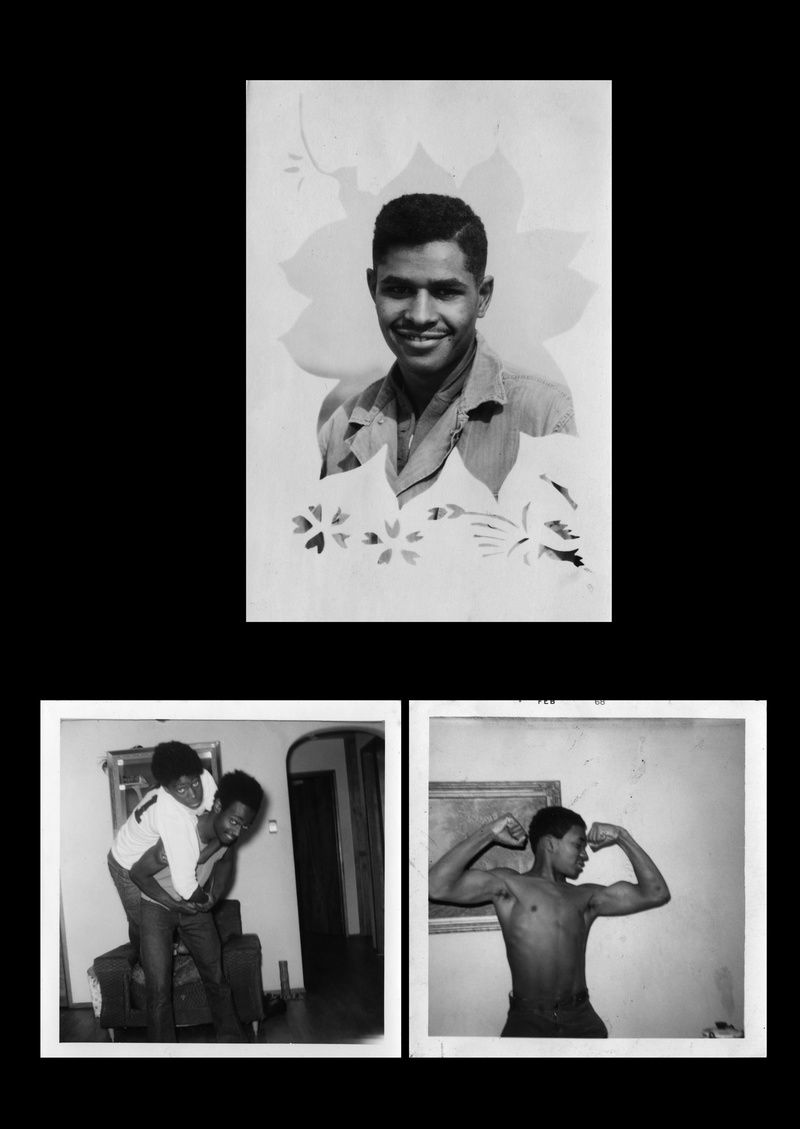

For most of the history of art, movies, magazines, books, and any material that documents Western visual culture, black people have been missing. There’s a visual language we inherit from white supremacy, about the way we should see blackness, sexually, physically, and psychologically.

It is Kehinde Wiley who, among other artists, is trying to explore and

reconfigure “how black identity is constructed, consumed, and manufactured.” He

has broadened his approach to include an international set of people of color,

who share a similar quality to the black folks he first went out to take

pictures of (which eventually turned into paintings) in Harlem and his native

South Central Los Angeles. Embedded in every picture are the complications of

the lives his subjects live.

Take Officer of the Hussars. In the naturalistic painting, a young black model he street cast in Harlem (as he typically does) replaces, the military official first seen in the eponymous 1812 Theodore Gericault work, wearing Timberland boots, blue jeans, and a white tank top so tight you can admire his physique. He rides a horse, wielding a sword, the black male fully human on the canvas. The picture transfers the power historically reserved for depictions of whiteness to an unassuming black Harlemite, allowing him to ask a simple question of us: When you look at me, do you see me? The query has proved to be a matter of life or death for black women and girls, boys and men, and trans folx.

Born in LA to a linguist mother who raised Kehinde and his five siblings alone, he has spent the last decade and a half living in New York and Beijing, painting ordinary people of color, prolifically, from all over the world. His grandiose portraiture, found in places like the Met, mixes the stately conventions of traditional European painting with the contemporary vernacular of hip-hop, queer, and black subjects. As he documents the unseen, his pieces are, truly, like nothing art has ever seen.

The first time I saw Wiley’s work in person was in 2015, at the Brooklyn Museum opening of a traveling retrospective, Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic. The art that floored me was not his paintings of the hardly seen black or brown gay men, like me, but his representations of black women. In a series of works entitled Economy of Grace, he painted black women from Harlem and the Bronx in white Givenchy dresses designed by Riccardo Tisci. I remember standing before the painting, The Two Sisters for a long time. I looked at the way they caressed each other, gazing directly at me, so self-assured. It was hard to find remember an equally compelling image in popular culture. So powerful, so beautiful, so free. I wondered, if it had affected me this much, what it must’ve meant for black women to see these reflections.

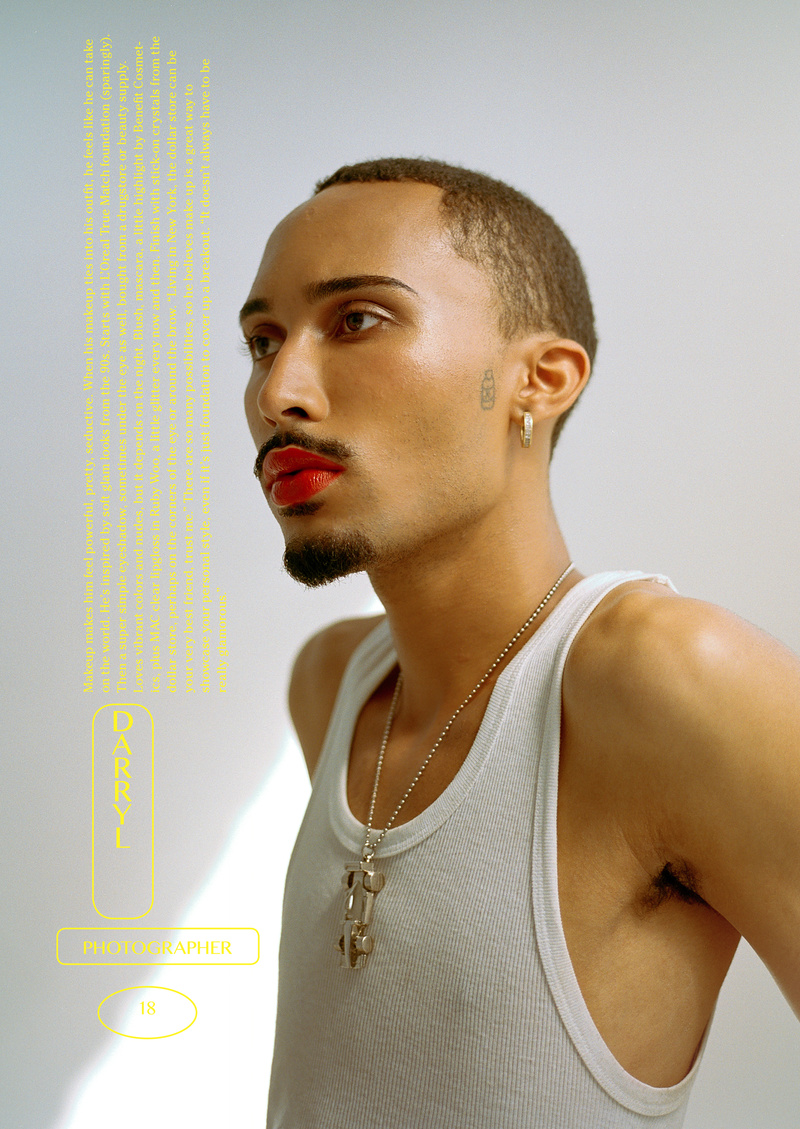

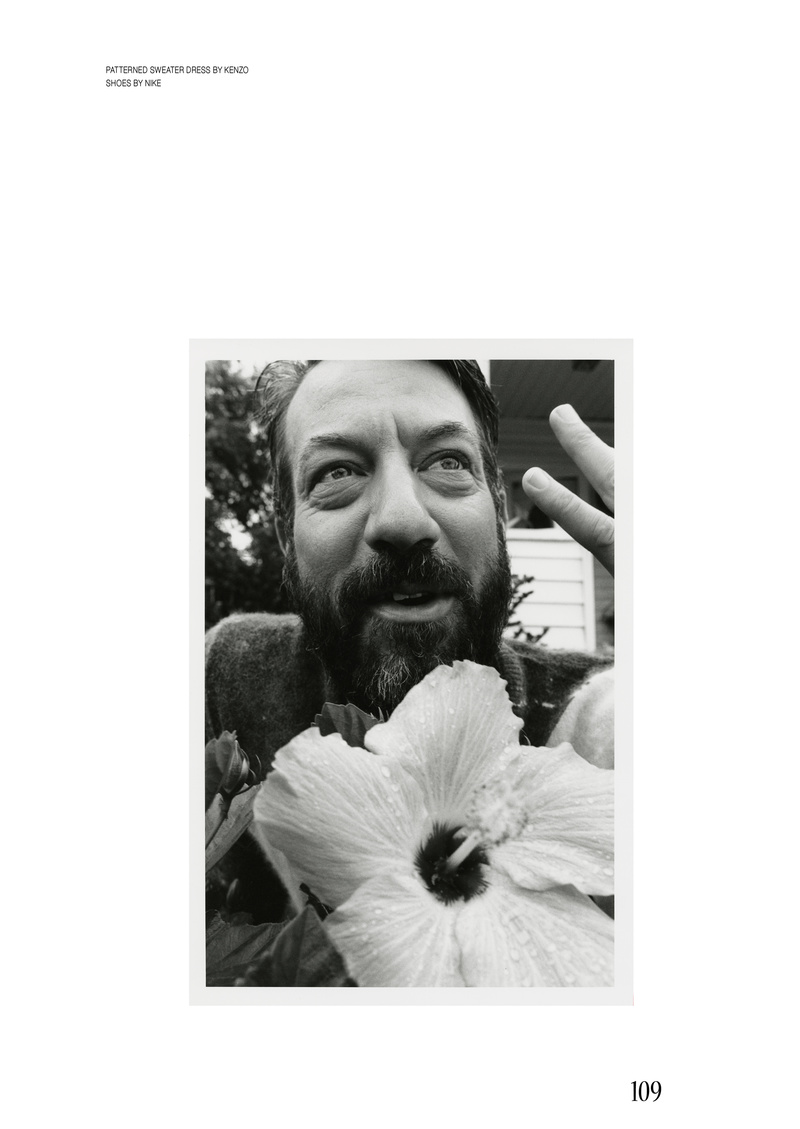

In person, Mr. Wiley appears like one of his paintings: black and heroic, in bespoke suits patterned with the ornate, decorative textiles often found in his paintings. Here in conversation, we talk about Kehinde’s memories, his anxieties, and his effort to combat the two-dimensional renderings of black life in America.

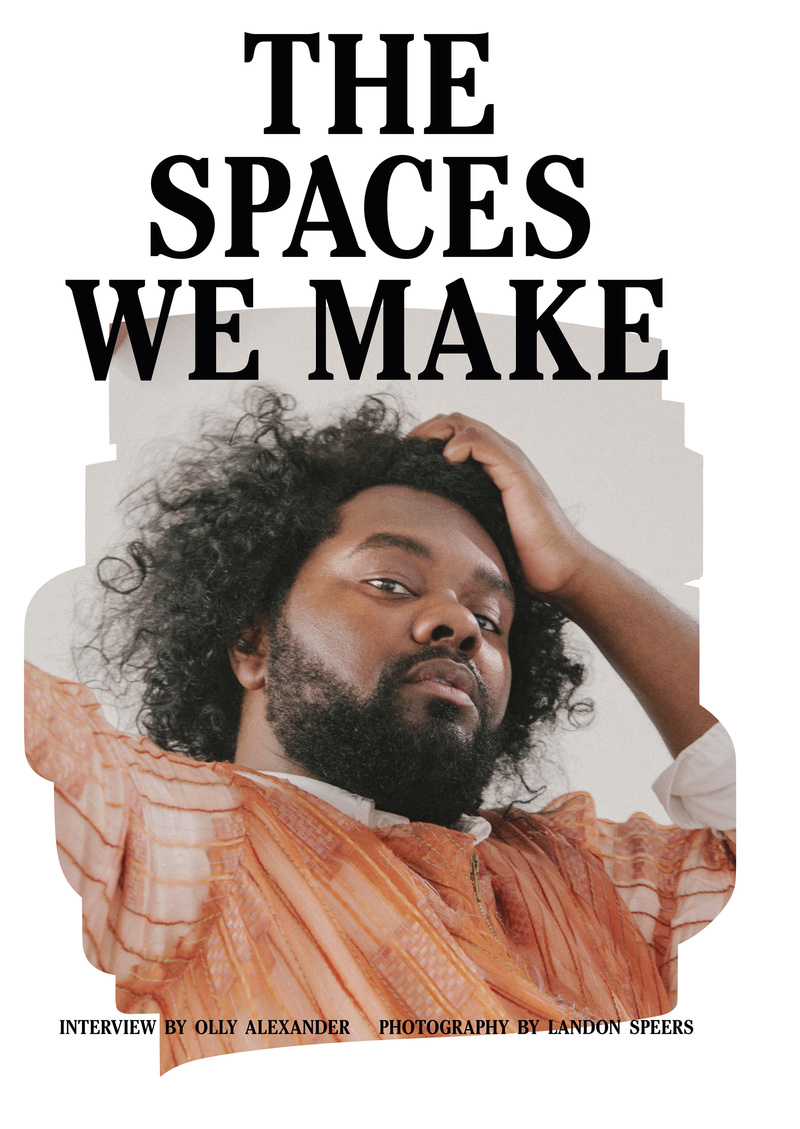

The first time you listen to Tunde Olaniran, expect an assault on the senses. You will hear a thumping beat, a foreign drum, some clap sounds. Then it feels like trap, with sirens and horns, like an afro-inspired M.I.A. Hold up, is he sampling Sweet Charity? And wait – are those tropical bird sounds?

The music of Tunde is much like his outlook on life – eclectic and uninhibited. He styles himself excellently (duh, as you can see), wearing shiny tunics and lots of dangly things. He changes his hair once a quarter. He art directs visual hire-wire acts in his videos and shows. He talks to his fans, colleagues, his producers, and collaborators all the same way: like friends at a bar. His generous laughter and saucy sense of humor feels married to the kind of music he makes, and at the same time, very different.

You could code his music as angry or “political,” but to Tunde, he’s just dealing with the simple subject matter of an everyday life. Tunde is from Flint, Michigan, a town you recognize from headlines because of a continuing city-wide water crisis due to lead contamination. This is a consequence of both state and federal neglect, and also environmental racism. (The city is 56% black.) In the face of this, Tunde’s lyrics, which touch on subject matter like gentrification, homophobia, systemic prejudice, and privilege, could be read as “advocacy” or “transgressive.” But it is that very assumption that Tunde challenges. Even his new single, “Symbol,” a light bop about his body and the bodily agencies we create around weight and color, is really only stating his own truths: “My body is a symbol / My body is a symbol.” Can one really transgress by simply living, by pursuing a life uninhibited, unsymbolized?

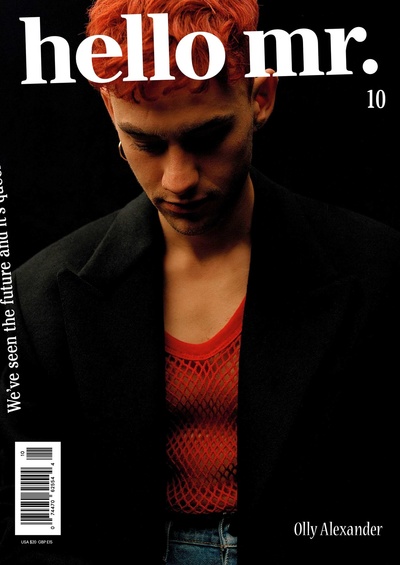

Here he is, in conversation with his internet friend (and international queer treasure) Olly Alexander of Years & Years, as they talk about their music process, the women they uphold, and the kinds of experiences they create for their listeners.

Olly Alexander: Tunde, tell me – Where are you right now?

Tunde Olaniran: I’m at home in Flint, getting over a raucous night. I just got out of bed and pretty much threw myself on this huge sectional. I haven’t seen the Mariah Carey documentary yet, but the promo is just her lounging on furs. I feel like I’m the budget version of Mariah Carey on a corner of my couch. I have this big dresser with all of my dancer’s costumes in it, and I’ve been picking out tour looks. There’s all these sequins and random costumes. it looks pretty hilarious.

OA: Wow. I think that is as close to Mariah Carey as anyone could hope to get.

TO: I’m probably closer to Mariah than anyone in Flint right now.